When Arsenal won the Premier League in their 2003/04 ‘Invincibles’ season, it symbolised the dominance of both them and Manchester United since the Premier League began. Between them they had won 11 of the 12 Premier Leagues that had gone before. But the Premier League’s power dynamic was about to shift.

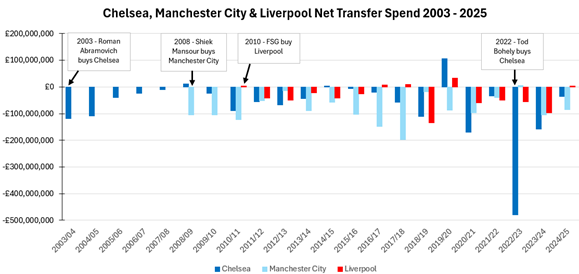

In 2003 Roman Abramovich had bought Chelsea and the Russian billionaire changed the financial landscape of English football overnight. Backed by his vast fortune, Chelsea embarked on a period of aggressive spending and managerial churn, with the club willing to absorb heavy financial losses in pursuit of silverware. Between 2003 and 2008, Chelsea spent over £390 million on transfers, incurring a net loss of more than £300 million. Adjusted for inflation in 2025, that outlay would equate to around £700 million, with a net transfer loss of approximately -£540 million.

If Chelsea pushed the boundaries of owner-funded ambition, Manchester City took it even further. When Sheikh Mansour acquired the club in 2008 from former Thai Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, City embarked on a state-backed football revolution. The strategy wasn’t limited to signing elite players – it extended to long-term capital projects and structural overhauls across the club. In the five years following the takeover, City spent £542 million on transfers, which, adjusted for inflation, is equivalent to around £800 million today. Their net transfer loss over that period was nearly -£595 million, setting a new benchmark for financial muscle and how much billionaire owners were prepared to spend.

In contrast, Liverpool’s journey under Fenway Sports Group (FSG) has been built on sustainability, smart recruitment, and financial prudence. FSG – then known as New England Sports Ventures – acquired the club in 2010 for £300 million from the troubled ownership of Tom Hicks and George Gillett. In 2011, they rebranded as Fenway Sports Group and introduced a philosophy that echoed the “Moneyball” model: data-led decision-making, value-focused spending, and long-term squad building.

Their approach was evident early on. In the 2010/11 season, Liverpool actually made a modest transfer profit of +£4.5 million. Over the next five years, the club recorded manageable transfer losses, reinvesting wisely rather than speculatively. In 2014/15, the club spent significantly, though partially offset by the £65 million received from Barcelona for Luis Suárez.

The turning point came under Jurgen Klopp. The model became more refined: buy young, high-potential players and sell at peak value unless they could become long-term core assets. In January 2018, Liverpool sold Philippe Coutinho to Barcelona for £142 million and immediately reinvested £75 million in Virgil van Dijk. That summer, Alisson Becker was signed for £67 million, another transformative purchase. Crucially, these were not signs of a spending spree, but of strategic reinvestment.

Between the 2016/17 and 2017/18 seasons, Liverpool also brought in Georginio Wijnaldum, Sadio Mané, Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain, Mohamed Salah, and Andy Robertson – all players who would form the core of a world-class side. Remarkably, despite these signings, the club posted a combined net transfer profit of £16.9 million over those two seasons. This highlights how Klopp and FSG worked in sync, moving on unwanted players for profit and targeting quality acquisitions that aligned with the manager’s philosophy.

As the financial data shows (see table), Liverpool’s two consecutive net profits helped set the stage for a calculated splurge in 2018/19, which saw the club record its largest-ever net transfer loss of -£133 million. That season, Liverpool won the Champions League, suggesting that FSG recognised the moment to go all in after years of careful building.

In 2019/20, Liverpool once again posted a net transfer profit of £32 million in the transfer market yet won the Premier League. Over the next four years, they added two League Cups, an FA Cup, and reached the Champions League final in 2022. The club’s ability to continue competing for top honours without consistently being among the biggest spenders underscores the success of their model.

The table shows a pattern has emerged. Chelsea’s early years under Abramovich were marked by extreme investment, which then gave way to a more restrained period between 2005/06 and 2009/10. That was followed by another wave of heavy spending from 2010/11 to 2013/14 and then the cycle repeated.

At Manchester City, the first three years after the takeover (2008–2011) were characterised by rapid squad overhaul. A brief period of restraint followed, but the arrival of Pep Guardiola sparked a new wave of investment, aligned with long-term footballing philosophy and infrastructure. Manchester City made a slightly less transfer net loss in 2018/19 but was replaced by nearly -£100 million transfer net loss in the following season. This repeated itself in 2022/23 when City made a slight transfer net profit but again was replaced by significant net transfer loss in 2023/24. It can be argued even Manchester City are now offering a more careful approach to their transfer business in recent years.

Liverpool may also be taking notice of Chelsea’s recent approach to transfers since Todd Boehly’s takeover in 2022. Under Boehly, Chelsea posted a staggering net transfer loss of -£479 million in 2022/23, followed by a further -£158 million loss in 2023/24. While spending was scaled back slightly in 2024/25 with a more manageable net loss of -£36 million, that restraint appears to have laid the groundwork for yet another transfer spree at Stamford Bridge in 2025. Chelsea’s recruitment model has leaned heavily on long-term contracts to spread the cost of transfer fees through amortisation—a strategic attempt to stay within the Premier League’s Profit and Sustainability Rules (PSR).

Liverpool, by contrast, made a modest net profit of £4.2 million in the transfer market last season. Combined with over £80 million earned from Champions League participation, a Premier League title, the announcement of a lucrative new kit deal with Adidas and the return of Michael Edwards who spearheaded Liverpool’s transfer spree in 2018/19, FSG have appeared to have positioned the club for another round of major investment. After the appointment of Arne Slot as manager a year ago it could mark a new cycle echoing the summer of 2018/19, when Liverpool heavily backed Jürgen Klopp following a frugal previous season.

In real terms, accounting for inflation in 2025, Liverpool’s net transfer loss in 2018/19 amounted to -£174 million, a figure the club could very well approach or go over by the time the current transfer window closes on September 1st. All signs suggest FSG are once again prepared to invest heavily at the right moment, backing their new manager in a way that mirrors the club’s most successful modern era rebuild.